How to Connect in a Reconnected World—with Cal Newport

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Overnight, technology essentially became our only means of communication. Face to face interactions – meetings, conferences, networking – were immediately replaced with Zoom coffees, happy hours and team meetings. It took adjustment, but we adapted.

Now, as we re-emerge and navigate a new normal, many are struggling to reconnect outside of the confines of their computer screens and the safety of their home offices. This episode will explore how to create sanity for yourself by approaching communication is a more structured way and taking control of your technology.

Learn the benefits of a digital detox and ways to shift your workplace away from “hyperactive hive mind” communication so you can get back to the basics of human connection.

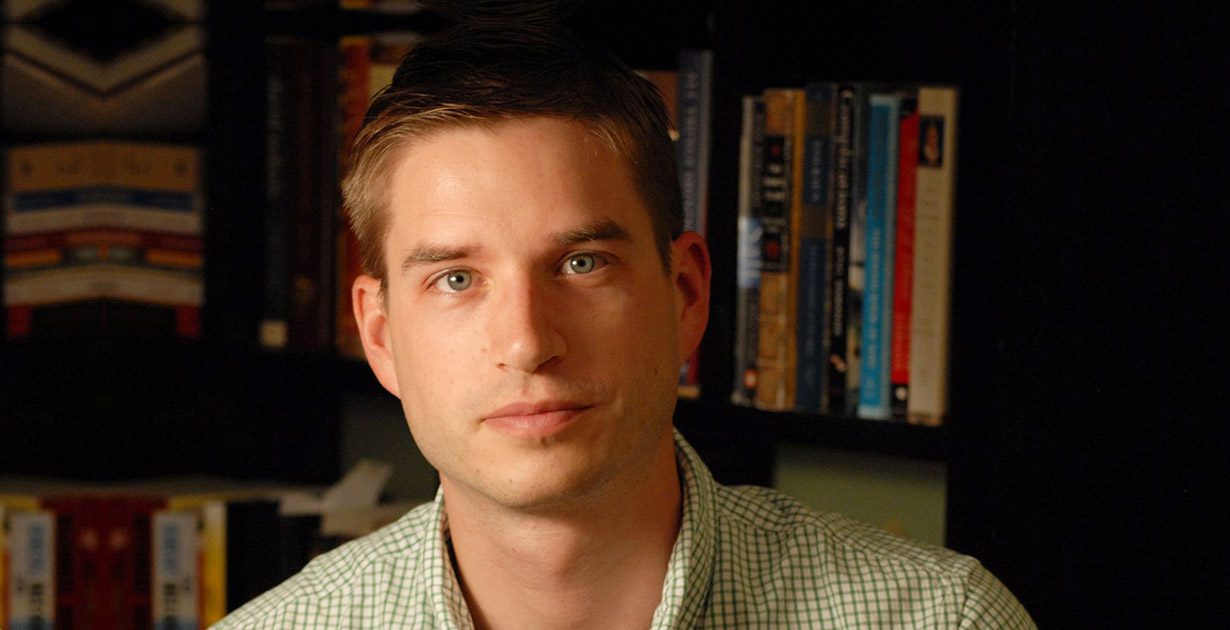

Cal Newport

CAL NEWPORT is an author and assistant professor of computer science at Georgetown University, specializing in the theory of distributed algorithms. Newport is the author of Deep Work, where he argues that the ability to focus without distraction is a superpower in the multi-tasking, internet-obsessed 21st century economy. In his newest book, A World Without Email, he proposes a bold vision for liberating workers from the tyranny of the inbox and unleashing a new era of productivity. In Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World, Newport proposes a bold solution: a minimalist approach to technology use by reducing the time you spend online. His book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, argued for the development of skills and craftsmanship rather than relying on “passion” as a career compass. Newport earned his Ph.D. from MIT in 2009. @calnewport2

Celeste Headlee

Additional Resources:

- Get FREE SHIPPING when you purchase any of Newport’s books from our independent partner bookstore, Bookpeople

- Learn more from Cal Newport (& sign up for his newsletter!) at CalNewport.com

More from Women Amplified:

- Sign up for Women Amplified episode alerts and you’ll get an email every time we have someone amazing for you to hear from.

- Register Now for one (or all three) of our upcoming virtual fall Conferences:

- October 7th Texas Conference for Women, featuring Malala Yousafzai, Ali Wong, Indra Nooyi, and more!

- November 10th Pennsylvania Conference for Women, featuring Simone Biles, Glenn Close, Laverne Cox, Simon Sinek, and more!

- December 2nd Massachusetts Conference for Women, featuring Regina King, Chloé Zhao, Selma Blair, and more!

Cal Newport Interview Transcript

Celeste Headlee:

I wanted to start with what may or may not have gone wrong over the pandemic. I feel as though there was a number of choices people could have made when so many of us ended up working from home. And I wonder, looking back, what worked and what didn’t?

Cal Newport:

Well, I think one of the big lessons of the pandemic when it comes to work and especially work in different locations is simply replicating with technology what happens in the office remotely. So saying we have the ability to talk to each other when we’re remote, we have the ability to give each other files and send messages remotely, did not add up to the office being faithfully simulated remotely. What seemed to have happened during the pandemic is that the informal ad hoc nature of the way we typically work these days in office work where a lot of things is just back and forth messaging and figuring things out on the fly gets even worse when you bring people out of the office.

Cal Newport:

And so what a lot of people experienced was more messaging, more emails, more Zoom, more Slack, and it became even more overwhelming. So the message I came away from looking at what happened during the pandemic is that we need more structure to how we work. We actually have to start thinking through things such as how do we keep track of who’s working on what? How much should people be working on? What is the processes through which we communicate about work? When and where do we communicate it? We have to do this thinking and in its absence, things can really spiral out of control. And I think we saw a lot of that actually happening when we abruptly brought everyone out of the office.

Celeste Headlee:

It’s interesting because so many things were hypothetical up until March of 2020. Many people such as yourself who work in this space of technology, how we use technology, what role it plays in our lives, had given us warnings this could happen, this might be the result of this. And then we actually saw it on the ground happening. I wonder if anything surprised you by the way we coped with remote work, and especially with having to connect with one another largely through our screens.

Cal Newport:

Well, one thing I got wrong is early in the pandemic, I wrote this big article for the New Yorker that talked about the history of remote work and what we might expect as the pandemic went on. And I made this point that the pain factor is going to be high. Because we’re so unstructured in how we work, if we just go abruptly remote without any other work about our processes and our workflows, we’re going to get even more overwhelmed. This can be very painful. And I optimistically then said, maybe that will be the pain point required to finally get serious about asking and answering these questions of, well, how do we actually structure our work? Maybe it’s time now to get more thoughtful about it.

Cal Newport:

That was too optimistic. We didn’t do that. And what seems to have happened is there was such multifaceted pain from the pandemic that it didn’t put us in a mindset of, ooh, how do we resolve this pain point? It put us in a mindset of we’re going to suffer. This is a period of suffering. This is one of many things that we’re suffering through in this period. So it was not inspiring action. We were already in a mindset of hunkering down. And so not much change. And I’ll tell you, my prediction is unless we take pretty strong steps to rethink how we work, there is going to be a gravitational pull towards the old way of in-person work that is going to exert a force that will get us in about 12 months from now back to a very similar state to the early 2019. That it will pull us right back into that.

Cal Newport:

We’re not going to have a sustainable change to what our workplace looks like just by announcing, okay, now we have changed our policy. Now we can be remote three days a week. Now we’re going to let anyone be remote. We have to do the other work of how do we redefine work so that remote actually functions.

Celeste Headlee:

Are you having these conversations with yourself about your own work life?

Cal Newport:

Well, I’m having this conversation with let’s say various companies who are thinking about this, who have read my material and they want to answer this question properly. I have a big conference call tomorrow with a company that will remain unnamed where we’re going through exactly this question because they’re very worried about it. In my own life, yes and no. I’m a professor. Professors, it’s a different type of job. It’s a little bit idiosyncratic. So there’s very little you can actually generalize from our weird job to normal type of work. But this is going to be a divide. I think there’s going to be the teams and organizations that think what drastic changes do we have to make to the nature of what we mean by work in order to go forward with something different, and those who say what policy should we have in place post pandemic. And that latter group, I think, is going to end up right back where they were.

Celeste Headlee:

I wonder if you could tell us what your advice is, and there’s two different types of advice. There’s the advice that it sounds like you’re giving to leaders how they can think about this moment as a reset button and how to do this the right way. But I actually want to start with what a worker can do. How does a worker advocate for themselves and advocate for creating a new relationship between personal and work life?

Cal Newport:

The key factor here and the factor that often gets missed is the underlying processes or workflow by which things get done. So where progress happens in terms of really changing your relationship to work and where you do the work and when you do the work, all of that ultimately needs to come from renegotiating how the work itself actually takes place. When we focus at the high level of when am I working or how often am I checking email or how many meetings should I be in or what days do I need to be in the office, when we just look at the high level, this is often ineffective because the source of friction that brings us back to the old way of working, which is not that great, is that the underlying implicit processes or workflow that we deploy just doesn’t allow for people to work at different hours, for people to be completely separate, for people to have these different types of days.

Cal Newport:

And so even when you’re thinking about work as an individual worker, you need to look below the surface and say, okay, for the things I do on a regular basis, implicitly how do we actually right now coordinate and organize that work? And for most people in most jobs, the answer is just, well, we just rock and roll. We email and slack and grab people in the hallways. We just try to figure things out. As long as that is the answer to the question, it is very difficult to do anything beyond nine to five I’m here just busy and probably afterwards as well. We got to renegotiate that underlying process or workflow if we want a substantial change where we start to figure out, okay, for this type of work, when does the information come in? When and how do we talk about it? When are the decisions made? And then what communication form are decisions made? We have to actually add this structure. That’s the way we have to start thinking.

Celeste Headlee:

I mean, looking through some of the advice you’ve given before, let me tell you how I interpreted that personally and then you can correct me where I get it wrong. So essentially it sounds like what you were asking me to do was sort of separate what are the tasks I need to accomplish. Like, what are my job duties? And then how have they gotten done in the past, in what ways was that method of work not serving me or making me more productive, and how could I actually intentionally craft my workflow so that I am doing the specific things at specific times for a reason. Is that accurate?

Cal Newport:

Yes. And also communication about the work itself gets structured to get away from if you need me, grab me. If you have something you need, just let me know. We’ll just go back and forth with messages to figure things out. So the best configurations for most work almost always are going to be configurations that minimize the need to see and respond to unscheduled messages.

Celeste Headlee:

Interesting. Why do you say that? Is that simply because we spend so much time on email every day?

Cal Newport:

Yeah. This gets at the heart of the idea from my most recent book, A World without Email, which is the implicit workflow that we typically use in modern office work is what I call the hyperactive hive mind, which is let’s figure things out on the fly with back and forth unscheduled messages. This could be an email. This could be in Slack. This could be in Teams, agnostic to the medium. But the idea that just back and forth unscheduled messages is how we work everything out. That’s the hyperactive hive mind. There’s two reasons why it’s a problem. Neurologically speaking, that requires that we check these channels all the time. And it’s not because we’re addicted to email. It’s not because we have bad habits. It’s because if we have two dozen different asynchronous back and forth conversations going on, which are pretty urgent, we have to keep checking because if we don’t, they will all get delayed.

Cal Newport:

If we have to do five or six back and forth messages to figure out when we’re meeting later today, those messages have to get exchanged this morning, which means I have to keep checking. And now that one conversation has created 20 or 30 email or Slack checks just to get that one thing done. You multiply that by a couple of dozen different ongoing interactions and we get to a state where we have to constantly check these channels. Now, if we had a parallel processor style brain, that would be fine. We could dedicate one part of our brain to just monitor these channels and communicate and another part of our brain could focus on the actual work.

Cal Newport:

In fact, this is what computers do. They are hooked up to networks. They have a thing called the network interface card that does nothing but deal with communication on the network. And then a main processor that does the main computation. Our brain can’t do that. It can only do one thing at a time, and it is a messy long-term process to change our focus from one target to another. So if we try to check inboxes or slack or email once every five or six minutes to keep up with all these ongoing unscheduled conversations, our brain is constantly in a state of partial shifting of attention, drastically reduces our cognitive capacity, makes us anxious, and gives us a massive amount of fatigue. That’s why we basically run out of steam by one or two in the afternoon and are just left just checking channels. It’s just not how our brain functions.

Cal Newport:

So unscheduled messages that have to be responded to is really a productivity poison. Our brain can’t do it. And then the other issue is if that’s how most work happens, you have to be involved in those conversations, which means you have just locked yourself into really prescribed hours. It’s very hard to get away from being stuck to a screen during work hours because you constantly have to be part of this back and forth asynchronous trip. So more radical or interesting forms of work; working different days, outcome-based work, working at different parts of the day. All of this becomes almost impossible to execute if that hyperactive hive mind is ultimately how things get done. So it really is at the core of a lot of our problems with modern office work.

Celeste Headlee:

I mean, one of the things that I have done over the pandemic is I’ve started checking my email at like nine in the morning and two or three in the afternoon, and that’s it, like that’s in my signature. And I have discovered that a lot of people who felt their emails were urgent found when it took hours for me to get back to them that they weren’t actually as urgent as they thought. And I wonder if you find that as well in your research and your work, that we have a false sense of urgency about things.

Cal Newport:

Well, there’s two tracks of issues going on here and they’re both important. So there’s the unnecessary sort of behavioral tips that we have that can be just solved by changing our usage of the tools. And I think that includes things like maybe we think some messages are more urgent. Maybe we check things more than we need to. Maybe we put too much value on quick response time. And these are things that can be fixed with individual behavioral changes. And I think there is definitely ground to be made up there. But it can only get us a little bit of the way towards a much better working territory. And that’s because fundamentally, if the hyperactive hive mind is how your organization collaborates, it is rational that you check these things all the time.

Cal Newport:

That for a lot of people, you can’t batch to 9:00 AM and 3:00 PM because there’s two dozen different back and forth conversations happening and five or six messages have to be exchanged and that probably has to happen in the next three hours because you have to settle on what you’re going to tell this client at the call at three. And in order for those five or six messages to get exchanged, you have to keep checking to wait for their response to come back. And now this one conversation is going to create 25 inbox checks in the next three hours.

Cal Newport:

So I think the reason why just focusing on how we can change our relationship with the tools or just changing norms in the office, let’s change our culture around response time, let’s change our culture about when we expect to hear back, this never has been able to actually get us towards a solution and it’s because as long as the hive mind is the underlying way that we collaborate, most people most of the time really can’t get away from having to interact with those channels all the time. That’s just actually how their work happens.

Celeste Headlee:

What is the alternative? I assume that it has to be a broader instead of an individual solution. It’s going to have to be a solution for an entire workplace. How do you stop that habit of getting work done by going back and forth and back and forth?

Cal Newport:

We have to replace the hive mind. This is where we get back to getting specific. Okay, here is something we do as a team. We produce marketing white papers. We keep up with client questions about our consulting services, whatever, you list out these things. How do we as a team actually collaborate on this? And if you haven’t thought about this before, the answer is probably just a hive fine, whatever, we rock and roll, we go on email. Now you say, well, let’s get more specific and put in place a specific alternative that talks about where the information comes in and goes, who works on it, how we assign it, how we talk or communicate with each other when decisions need to be made, when that communication happens and on what format.

Cal Newport:

You work that out as a team, and you now have in place an explicit alternative for just rock and rolling on email or slack and you basically have to do this thing by thing that you do. Now, even as an individual, however, you can make a lot of progress even if your team wants nothing to do on this. Just starting to think about your work from the perspective of I do these seven things, how do I actually want to do these seven things? Just focusing on what you can control, you can actually probably drastically reduce in many cases the amount of unscheduled messages needing to be responded to that’s involved in actually implementing these different things you come back to again and again. So the mindset shift, oh, here’s the goal, build alternative processes that reduce unscheduled messages. Once you know that’s what you’re trying to do, there’s a lot of open water here that you can pretty quickly traverse.

Celeste Headlee:

What do we do about emails and things that come in after hours? I have to assume the vast majority of people are not being paid to be on call 24 hours a day, but we behave like we are. So how do I as an individual, if I get an email from my boss at 9:00 PM, I’m going to feel like I need to respond to it.

Cal Newport:

The emails after hours are almost always a consequence, again, of this hyperactive hive mind way of working because basically if all we’re doing is trying to attend all these back and forth conversations to make progress on work, we get overwhelmed with these ongoing conversations. And we end up, especially when our day gets filled with Zoom, when our day gets filled with meetings, having to go after hours just to keep up with all of this. That’s the source of it. It’s why, I mean, I think it’s a scandal that non-industrial productivity in this country has stayed stagnant throughout this whole communication revolution, but it’s not really stagnant. We’re adding all of these extra hours off the books. So really it’s been falling. We just don’t actually capture that when we’re actually working on these metrics.

Cal Newport:

So short term, don’t answer the emails after hour. They’re coming because that person has been in Zoom meetings all day and has to get through the backlog because it’s going to all begin again the next day. They don’t actually probably even want you to respond at 9:00 PM. They’re trying to get that inbox back down close to zero. Long-term, we shouldn’t have to do that at all. This is what you can get to if we get away from the hive mind. If the things you do we have structure for when that communication happens that we figured out and where it happens, well, you’re not going to have communication that happens at 9:00 PM. You’re not going to have 300 emails that you have to get through. So, you solve this underlying workflow problem. These type of indignities, the me having to add four hours of work outside of what I’m paid to do, can really begin to dissipate.

Celeste Headlee:

I wonder what you feel about some of the things that occurred during the pandemic and why they happened. For example, we know that, number one, meetings got shorter and before any of us thought that was good news, it turned out they were shorter because there were so many more of them. The number of meetings exploded. Why do you think that is? When we began meeting over video conferencing, why did we set up more meetings?

Cal Newport:

Yeah, it really did get out of control. I kept hearing from readers who literally their problem was when do I have time to go to the bathroom during the day? That’s what it had gotten to, because it would be six hours packed back to back. It really got out of control. I have two explanations. One, I think we underestimated the degree to which when we’re in the office, there is the subtle productivity heuristics that gained us a lot of grounds. We could grab someone in the hallway. If we were in a meeting for one thing, we could chat with people before or after that meeting stopped. We could watch out our office door until we saw someone pass that we needed to talk to and say, hey, wait, come in here for a second. Very quick sort of informal synchronous conversations was actually accomplishing a lot of work.

Cal Newport:

When we went remote, all of those productivity heuristics went out the window and we had no other choice but to actually get people together in a meeting. And once you’re going to schedule a meeting, well, it’s not just going to be six minutes long, it’s going to be in increments of 15 or 30 minutes. The other thing I think that happened is the friction involved in pulling together a meeting got reduced and this type of thing matters. I mean, if I’m going to call a meeting in a real office, first of all, there are some logistical friction. Maybe I have to reserve a conference room. I have to go talk to the admin and make sure the conference room is open.

Cal Newport:

And then there’s a social capital cost. I have to see you all walk across the office, come to the conference room. You had to get coffee, you’re coming in, I have to look you in the face. I feel a little guilty about this. I better have a good reason for bringing you here. With Zoom button, the friction’s gone. I can just, why not boom, boom, boom. So that started happening. So I think those two things coming together, I think that really helped explode it.

Cal Newport:

And the third thing I would throw in there is that, and this is something else I missed, the shift to remote work created a lot of new work because in addition to us being fully remote, everyone had to figure out on the fly how their company was going to operate remote. This threw a lot of people for a loop. Like how do we produce the magazine? How do we deal with client? How do we do a seminar business when we can’t do it in person? So it actually generated a lot of new work. And again, I missed that too when I was trying to predict what was going to happen. We got so overloaded with new work and we just, how do we even deal with this? Where do we even start? And the answer was like, I guess we all just get on a call and talk about it. So those three things together, it created really a perfect storm of meeting terribleness I guess is one way to describe it.

Celeste Headlee:

It was meeting terribleness. And I feel like people are going just from one… Here’s something that I got wrong, which is about before the pandemic, I would recommend people use video conferencing as a replacement for all the emails. I certainly do not do that anymore because research shows how exhausting Zoom is. But the other thing is that remote work meant people were not even taking breaks in between meetings, as you say. So as we move forward, how do we maintain, if we’re able to, some days work at home without continuing this meeting madness you’re talking about?

Cal Newport:

Well, we have to get way more structured, including structure about communication. So it’s much clearer when communication happens. As you were talking about pre-pandemic, you were recommending video conferencing and that’s because synchronous communication, there’s a lot of overhead to set it up. But it’s incredibly efficient once you’re actually doing it, but there’s a huge overhead to actually set it up. So having more structured communication I think is really important. Here is regular status meetings that are highly structured and 20 minutes long, and so we can defer quite a bit of interaction to the next one.

Cal Newport:

Office hours is another way of sort of deferring and structuring interaction. Every day there’s a certain hour in which you know for a fact I am available. In fact, I’ll be in a Zoom room that you can just show up in. Now, you can start deferring quicker questions, shorter discussions to just grab me in my next office hour. So there’s a lot of things we need to do to make remote work sustainable. But just in terms of one concrete thing we can think about is getting more structure about when this communication happens. Getting us away from for each ad hoc thing that arises, let’s try to set up a meeting to discuss this. And so that’s just one thing of many that I think could free up a lot of space here.

Celeste Headlee:

From your point of view, is there a gold standard for work place habits? In other words, is the ideal a hybrid situation, is the ideal allowing someone to work from home all the time? What do you think here?

Cal Newport:

To me, the ideal is it doesn’t matter. That you have things set up in such a way that where and when exactly people are working is irrelevant. I think that is where we want to. Now, there are examples of this. A general sector where you can see this being much easier to do is in software development. Why are there been such great successes with fully remote companies for years in software development? Well, because they have a very structured approach to how they do their collaboration. They use agile methodologies where they have shared task boards where it’s crystal clear what needs to be done. They have strict work in progress limits. Like Celeste, you’re just working on this right now. Go do it in a sprint. They structure their interactions. Their interactions happen in these 15 minute called standing status meetings that are highly structured.

Cal Newport:

So there’s very little back and forth interaction between those meetings. So they’re very highly structured. So if you want to do this remote, no problem. You want to do this in person, no problem. You want to do this half and half, no problem; because you know how the work is structured and having the task board on a virtual task board using video conferencing for the status meetings works just fine. The other sector I look at is there’s a movement that’s been around since the early 2000s called results only work environments. These are environments where it is entirely outcome-based. When and where you work is entirely up to the individual. Are you at the movies in the middle of the day? Are you here on Friday? There’s no one that supervises and no one who cares. It’s all outcome based. And if you do this right, it actually does work.

Cal Newport:

I’ve been profiling some of these companies for an article I’m writing. When the pandemic hit, it was no factor. Nothing had to happen other than them just sending out a note saying, oh, by the way, the office building is closed. And what was their return? Their return strategy as office buildings opened was just sending out a note, oh, by the way, our building is open. If you want to go there, here’s the COVID precautions, because they had completely built their work around outcomes. Here’s what I’m working on. We’ve negotiated when and how we’re going to talk about it, and I execute. I either do it or I don’t. Whether you can see me in the office, whether I’m answering emails, none of this is that important. So I think there is radically different ways to work, but it requires a lot more structure.

Celeste Headlee:

In general, why didn’t businesses learn from those who had done this successfully in the past? I mean, as a journalist, I immediately thought about the fact that NPR has had remote workers everywhere. We call them foreign correspondents. We have worked well with those people for a very long period of time. We are extremely results based. You’re required to produce a certain number of minutes per month of broadcast news, and that’s what we focus on. But nobody came and asked, “Hey, how have you done this successfully?” And there are many, as you mentioned, of other companies who have done this for years, why didn’t we consult?

Cal Newport:

I think part of it is hard. So if you think about let’s say the foreign correspondents at NPR, I’m sure at some point a nontrivial amount of work and trial and error was involved in figuring out how that works. Okay, it’s you report in this way, it’s this many minutes, we have this type of system. And so in order to do that let’s say in April of 2020 for a company that has a lot of different roles is you have to basically go through that thinking, experimentation and trial and error for every different role in your company, and it’s hard. Companies don’t want to do that because it’s hard. And so what they want to do instead is like, can’t we just change a policy? Can’t we just say you can work from home three days a week, or it’s up to you if you work from home. Let’s just change a policy and email it out.

Cal Newport:

So I think it is really hard. And then we bring into it something I talk about in my last book. There really is a culture of autonomy in knowledge work where we think about how you organize and execute your work as been really up to the individual and the goal of management is to have clear objectives, like management by objectives. Here’s what you’re supposed to be doing, and make sure people have incentives to get the work done. But we don’t really want to think about how the work actually gets done. That’s sort of none of our business as managers is the philosophy there.

Cal Newport:

And then there’s a good reason where that came from, but when it gets overextended, as it is I think in knowledge work, we get in the habit of saying we don’t think about how work happens. Like to think about, well, you should just do… It’s based on here’s when we talk and the information goes into the system and you can pull it out of there. We only do that in very specialized cases. So we’re just not in the habit of thinking about work from the perspective of what are the systems and rules and protocols for how the work actually happens. We’re used to just saying that’s up to the worker to figure out. They can go buy some personal productivity books, our job is to assign work. And so I think in that culture, we just didn’t have the managerial muscles necessary to start thinking, how do we rethink and rebuild all these different positions?

Celeste Headlee:

And so we ended up into this place. Another one of the books that you wrote was called Deep Work, maybe 2016, a few years ago. It occurred to me as I was preparing to interview you that we are so far away from what you recommended in Deep Work. When they survey team members, and this is pre-pandemic, a ridiculous tiny minority said that they actually end up doing any kind of deep thought while they’re on the job. And now after the pandemic, when they’re just constantly going from one meeting to another where they have check-ins on slack and inboxes open at all the time, are we engaging in deep thought while we’re at work right now do you think?

Cal Newport:

Most people are doing basically zero because in order for something to count as deep work, it’s not just you’re concentrated on something hard, but you have to have a reasonable amount of distance from the last time you were focused on something else because as I mentioned before, context shifts reduces your cognitive capacity. So every time you look at an inbox, every time you look at your phone, you are inducing a context shift. You’re going to have what’s called attention residue for up to 15 minutes after that before you get your focus back. So deep work is not just about what you’re doing in the moment, but having some space from having done anything else so that you really are able to rev your mind up to its full capacity.

Cal Newport:

I have some pretty compelling data sets that say for most workers, the amount of this you do, so the amount of time during the day in which you are focused and have stayed focused on that without a distraction for at least the last 15 minutes is basically zero. That we just don’t do it. It’s an incredible waste of the cognitive resources here. We hire all these human brains. Human brains are the primary capital resource of a knowledge work organization. And if we’re going to use just really blunt economic terms, this way of working that we do today gives us an incredibly low return on that capital.

Cal Newport:

We would never tolerate this in another sector. If you were in the industrial sector, this would be the equivalent of running a car factory that produced one car per day. You would say you’re getting a terrible return in all this money you invested in the factory, you need to configure that factory better. This is what is happening with our brains. We’re paying a lot of money to get a lot of smart brains and then putting them in an environment where they’re miserable and can produce very little actual high quality cognitive output.

Celeste Headlee:

Does the individual worker do you think, the average worker, have the power to create an environment in which deep work is possible?

Cal Newport:

You can make it better. I think ultimately, this was the argument of the most recent book is ultimately until we get rid of the hyperactive hive mind, it’s going to be a difficult uphill battle. So you can make your conditions better. I mean, A, just recognizing deep work is different from the shallow work, B, recognizing that it has to be nontrivial durations without any context shifts. If you’re checking your inbox quickly, that’s not deep work. You’re actually really reducing your capacity. That’s really important. You can have negotiations with your supervisors. I’ve talked about this before where you say, “Here’s deep work, here’s shallow work. What is the ratio of deep to shallow work that is optimal for my job that’ll produce the most value?” And then figure out a plan for how you can hit that.

Cal Newport:

So there are examples of this where there’s these maybe two hour stretches in the morning and one in the afternoon where it’s announced this person is completely unreachable. So there’s things you can do. You can rewire your processes, the stuff you do regularly and say, how do I reduce unscheduled messages? There’s a lot you can do there. And now there’s less checking you have to do. But I think ultimately this is going to be a wholesale change in how we think about organizing knowledge work, moving away from the hive mind towards thinking explicitly about how we want to implement each type of work. That is the shift that has to happen before we’re really going to see consistently really good returns on all this cognitive capital out there.

Celeste Headlee:

Do you think we are ready to make this kind of revolutionary change, because really you’re talking about a revolutionary change. It’s an entire rethinking of the way we have done things for the past half century. And I wonder if you think we’re ready to do that.

Cal Newport:

I think we’re getting close, and here’s the big advantage we have. This is an optimistic view. I think there’s a natural pessimism about these types of changes happening because if we look historically, labor politics are typically looking at settings where there is an adversarial dynamic, let’s say, between managers and capital owners and workers. This was the case in the labor politics about the industrial sector. There’s an adversarial dynamic where what’s good for one group is bad for the other, and therefore we have to find ways to rebalance this. That’s not actually really what’s happening in knowledge work. Actually this hyperactive hive mind way of working is bad for everybody.

Cal Newport:

So it’s not a situation where like, look, it’s great for Jeff Bezos if his knowledge workers, all using the hyperactive hive mind, it’s bad for them and now we have to figure out a way of trying to rebalance these labor dynamics. It’s bad for everyone. Managers hate it, C-suite people hate it, the actual employees working in this hate it. It makes you miserable and very unproductive. You can’t produce much. So actually there’s a good deal of alignment with all of the stakeholders with the exception of maybe the company that creates Slack or the Gmail team. But outside of a few of these exceptions, basically everyone is aligned with we would love for work to be less of this hyperactive communication and more productive. We’d have less turnover. Our workers will produce more, our workers will be happier.

Cal Newport:

The main things that have been holding us back is, A, complexity. Now, of course, this is common. I mean, whenever we see leaps forward in how we conduct commerce, it’s usually the leaps forward are more complex and difficult. So getting over that complexity barrier is non-trivial. It’s much more difficult to figure out through experiment and trial and error and reflection these bespoke systems for all these different roles and all these different types of work. And then, two, we have this autonomy culture. We’re just not used to, in knowledge work, thinking about how the work actually happens. Too much of that we lay on the worker themselves. We put the word personal in front of productivity and say, look, it’s up to you.

Cal Newport:

We have to get past that autonomy mindset and we have to be willing to do some pain because it’s not easy to shift away from the hyperactive hive mind. But in the years since Deep Work was published, I’ve noticed a big change. When I talk to let’s say the investor community, when I talk to the C-suite community, this has shifted in the last couple of years. There’s potentially hundreds of billions of dollars of American GDP on the table if we could actually get the real value from the minds of all of these knowledge workers. So I think there’s a sea change happening right now where we’re getting closer to people saying, “I see the problem. It’s the way we work, not our habits.” Yeah. It’s going to be a pain to change it, but it’s a pain probably worth doing because my company will be 3X more productive. My turnover will be cut in half, my turnover will be a third as large. So I’m now more optimistic that in the next five to six years, we’re going to see pretty big changes in a lot of companies.

Celeste Headlee:

I wonder what your reaction was to the polls that show a large number of workers are willing to quit their jobs rather than be forced to go back into the office again every day. What do you make of that? Is that a good sign or bad?

Cal Newport:

Yeah, I saw that. It’s the Bloomberg Morning Consult poll. I mean, I think what this emphasizes is the urgency of trying to figure out a better way of making work happen, because here’s my big prognostication on this. And I’m working on a piece on this at the moment, so it’s really fresh on my mind. We can’t successfully dramatically change when and where work happens just by changing a policy. This is the crisis of our current economic moment post pandemic is there’s things about remote work, for example, that a lot of people like, and in particular, not having to synchronize their hours to work hours and not having to do the commutes and the flexibility it affords.

Cal Newport:

But in order for remote work to be sustainable at high levels, it’s not enough just to have Tim Cook change in an email what days you’re allowed to be remote. We really have to change the definition of work to be more outcome-based and more structured. As long as it’s the hyperactive hive mind just based on ad hoc back and forth communication, remote work will be worse than being in person. And the gravitational pull is going to pull companies back to in-person work and it’s going to push a lot of people out of the workforce because there’s these advantages they saw to this other way of working that they don’t want to give up.

Cal Newport:

So to me, that particular Bloomberg poll underscores the urgency of this question of what is our definition of work? How does it happen? We have to make big changes here. If now is not the time to face the pain of figuring out what is the equivalent of the foreign correspondent set up for a marketing copywriter, for someone in the HR department, for whatever, if now is not the time to do that, well, when are we going to do it?

Celeste Headlee:

I mean, I wonder if you’re also… You say you’re optimistic. I wonder if there’s also an equal amount of concern. I mean, you and I talked about this before in an earlier conversation, which was that we were in trouble before the pandemic began. There was already a burnout epidemic that the WHO had identified in 2019 and earlier. And a lot of that was due to problems with our work habits, problems with the blurring of the line between work and home life, problems with workers not feeling as though they’re actually getting things accomplished and not feeling appreciated. I wonder if you’re concerned that we’ll get this wrong and we will reach a tipping point.

Cal Newport:

Well, I’m optimistic at the five to 10 year scale, and then I’m concerned about the near future. I think at the five to 10 year scale, I am seeing the signs that we are going to move past the hyperactive hive mind. We’re going to start to get structured and explicit about how work happens. And this is going to be a monumental change. Sort of similar if we look back at the history of car manufacturing when they went from a craft method to the assembly line method, it completely changed what was possible with car manufacturing. So I think it’s going to be one of these massive changes that’s going to be very positive. It’s also going to generate a huge amount of economic growth, which rises all ships. I think that is all positive.

Cal Newport:

But I am worried about the short term because I’m looking at like how CEOs are reacting to returning to work and should we stay remote, should we not stay remote? There is no depth in the thinking I’m seeing. Everything is viewed through the lens of just policy. Like what is our policy? There is almost no scrutiny being paid in these public conversations about how the work actually happens and how that interacts with what’s successful or what’s not successful. It is a very shallow way of looking at this issue. And I do think people, a lot of people are at the end of their rope.

Cal Newport:

The hyperactive hive mind is out of control. It really is out of control. I mean, the idea that it’s almost like a cognitive portrait chamber, the degree to which you have to just keep up with all these asynchronous messages you’re left with no time to do anything else. It is a ridiculous way to work. I can’t believe we don’t realize how absurd it is. It would be like if you went to a car factory and they had turned all the lights off to save money on the electric bill and they’re so proud about like look at how efficient our electric bill is. And meanwhile, no one can see the parts they’re trying to put on the cars and they’re producing one car per day and the steering wheel is on the back, we would say, well, this is crazy. I mean, you’re saving money on the electric bill, but it makes you terrible at building cars.

Cal Newport:

It’s kind of what’s happening now. Like it’s easy and convenient if everyone figures things out on the fly with one universal communication tool, but we’re putting the steering wheel on the back of the car and producing two model piece per day. Like if we just step back, what we’re doing does not work and it is almost absurd. When you see someone who has to do Zoom for eight hours in a day, that should be in like a Kafka play. And yet we’re like, “Oh, I guess that’s just what work is.”

Cal Newport:

So revolution has to happen. But again, I come back to at least in this case, unlike other points in the history of labor politics, ultimately we’re all aligned. I mean, the thing, again, that’s keeping us back is not that this is bad for you but good for me. It’s that it’s just hard. It takes a pretty big push to overcome a large hill. So that’s where my midterm optimism comes from is everyone wants this change. I just did a conference call with 50 CIOs from Fortune 500 companies. They all want this change. They all know this, like let’s be on Zoom and email all day is a terrible waste of resources. And so we all want this change and that’s where my optimism comes from. But my pessimism is, I don’t think we fully realize what that means and what needs to be done tomorrow.

Celeste Headlee:

Before I let you go, I want to get just a couple more really concrete tips for the person who is an employee and at this point is probably stressed out, is probably overwhelmed, probably feels dread even at the prospect of looking at six Zoom conference calls on their calendar each day. What are just a couple even small things that they can do? For example, what if they quit social media? Will that relieve the pressure?

Cal Newport:

A little bit. But ironically, I think people are so busy with Zoom and email and trying to keep up with the workplace communication tools that they’re not even left with that much time to look at their phone. And so it doesn’t hurt to significantly structure or reduce your social media usage. But there’s a lot more direct, concrete things you can do about how you structure your work that I think can give you big returns in the short term.

Celeste Headlee:

If they are a person who is, again, like I said, had enough of Zoom, doesn’t want to see a video of themselves ever again, this might prevent them from calling friends. It might make them feel socially exhausted so they don’t go to a party over the weekend. Any advice on how to maintain social connection in a period of time in which we’re being forced to be perhaps more social than we want to be?

Cal Newport:

Right. Well, I mean, first of all, change the mode, do it in person. If your workplace is largely on Zoom, take advantage of the existence of vaccines to have a different mode of interaction, which is in person, or if it’s someone who doesn’t live nearby, use a telephone. You might say, well, I’m just giving up video, but it feels different. You can be on a call while you’re walking. You can be in the sunshine. And so changing the actual mode of interaction is going to feel like there’s some diversity from just staring at Zoom. So I think that can make a big difference.

Celeste Headlee:

Is there anything else I haven’t asked you that you think could be useful to our listeners?

Cal Newport:

Well, first I would just underscore when you’re thinking about your work, understanding that the real villain in terms of productivity is these context switches. I’d really like to underscore that point is that when you glance at something, you initiate a context shift that’s going to affect you for 10 to 15 minutes. So the whole game, when thinking about your work, should not be about how do I process things quicker? How do I organize my emails better? How do I get through more tasks? The real definition you should be thinking about is how do I minimize having to do context shifts when I’m working on something else? How do I do one thing at a time until it’s done and then move on to the next thing without having to have context shifts in the middle? So just knowing that’s your battle can really help.

Cal Newport:

Two, talk to the people you work with, talk to your bosses and say, “Look, here’s the deep stuff I do that’s valuable. Here’s the shallow stuff I have to do to keep the lights on.” Like what ratio do you want me to do? You tell me. If you want me to do zero of the deep work, okay, you have to tell me that’s what I want from your job. And if you think that’s not, then you have to tell me what ratio you want. And if we agree on a 50/50 ratio, for example, then we need to figure out how to make that possible. You would be surprised that when you get clear, quantitative and objective about this, how much change is actually possible, how all of a sudden your boss is like, “You’re right. Here’s what we’ll do. No Zoom before 12:00 for you,” or whatever it is, because now it’s coming from a very specific quantifiable place.

Cal Newport:

And then three, be willing to trade accountability for accessibility. The way you can essentially negotiate yourself out of just having to say yes to everything and be available all the time is to produce good stuff. That trade off again and again does play off is like, yes, I have a quota of what I can do. So I have to say no to a lot of things and I block off time for working, so I’m not available for the meetings. But the work I do, I deliver it when I say I’m going to deliver it and it’s good. This can often be traded for accessibility. If you’re not delivering that, then you could fall into a situation where a boss basically thinks like, “Look, I just need to keep on top of you. I need you to answer me because I don’t trust things are going to get done.” So those are three things I think to keep in mind when thinking about how to tame this beast of constant communication that is afflicting us right now.

Celeste Headlee:

Cal Newport, thank you so much.

Cal Newport:

Well, thank you, Celeste.