Power of Our Words and Actions

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

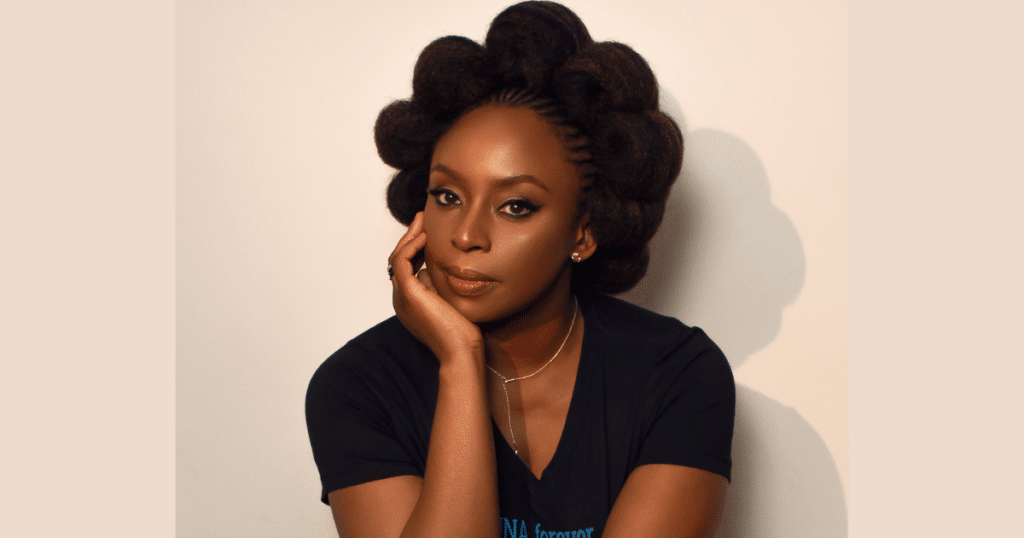

This episode features an extraordinary conversation between award-winning author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Americanah, Notes on Grief) and Target’s EVP and chief external engagement officer, Laysha Ward.

Spoken or written, words are a powerful vehicle to share knowledge, offer perspectives and influence others. They can be truths, facts, or alternatively, they can perpetuate negative thoughts, stereotypes, even fake news.

Recorded at the December 2022 Massachusetts Conference for Women, these two women explore Chimamanda’s journey to offer perspective around the power of words, acknowledging differences, and being fully inclusive. Learn how to avoid rushing to judgment and to truly understand opinions — even those that strongly differ from your own.

Our Guest: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is an award-winning author born in Enugu, Nigeria. She graduated summa cum laude from Eastern Connecticut State University with a degree in communication and political science. She has a master’s degree in African studies from Yale University, and in creative writing from Johns Hopkins University. She was awarded a Hodder fellowship at Princeton University and a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute of Harvard University. She received a MacArthur Fellowship, popularly known as the “genius grant.” She has received honorary doctorate degrees from 15 prestigious universities and colleges. Adichie’s work has been translated into over thirty languages. Her first novel, Purple Hibiscus, won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and her second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, won the Orange Prize. Her novel Americanah won the US National Book Critics Circle Award, and was named one of The New York Times Top Ten Best Books of 2013. She has delivered two landmark TED talks: The Danger of A Single Story and We Should All Be Feminists, which started a worldwide conversation about feminism. Her most recent work, Notes On Grief, an essay about losing her father, was published in 2021. She was named one of TIME Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World in 2015. In 2017, Fortune Magazine named her one of the World’s 50 Greatest Leaders. Adichie divides her time between the United States and Nigeria, where she leads an annual creative writing workshop.

Guest Host: Laysha Ward

Laysha Ward is an accomplished C-suite executive with thirty years of leadership experience at Target. In 2017, Ward was named executive vice president, chief external engagement officer, overseeing Target’s enterprise-wide approach to engage and deepen relationships with cross-sector stakeholders to drive positive business and community impact. In 1991, Ward began her career with Target as a member of the store sales and management team of Marshall Fields in Chicago. In 2000, she was named director of community relations and promoted to vice president of community relations and Target Foundation in 2003. In 2008, President Bush nominated, and the U.S. Senate confirmed Ward would serve on the board of directors of the Corporation for National and Community Service, the nation’s largest grantmaker for volunteering and service, which she continued to serve as board chair under the Obama Administration. Later that year, she was promoted to president of community relations and the Target Foundation. She serves on the Aspen Institute Latinos and Society Advisory Board and the Stanford Center for Longevity Advisory Council, is a member of the Executive Leadership Council, the Economic Clubs of New York and Chicago, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, The Links, and serves on the boards of Greater MSP, the Minnesota Orchestra, and the Northside Achievement Zone, as well as United Airlines and Denny’s Corporation for-profit board of directors. She received a bachelor’s degree from Indiana University, master’s degree from the University of Chicago, and an honorary Doctorate of Laws from the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs. She and her husband, Bill, reside in Minneapolis, MN.

Women Amplified Host: Celeste Headlee

Celeste Headlee is a communication and human nature expert, and an award-winning journalist. She is a professional speaker, and also the author of Speaking of Race: Why Everybody Needs to Talk About Racism—and How to Do It, Do Nothing, Heard Mentality, and We Need to Talk. In her twenty-year career in public radio, she has been the executive producer of On Second Thought at Georgia Public Radio, and anchored programs including Tell Me More, Talk of the Nation, All Things Considered, and Weekend Edition. She also served as cohost of the national morning news show The Takeaway from PRI and WNYC, and anchored presidential coverage in 2012 for PBS World Channel. Headlee’s TEDx talk sharing ten ways to have a better conversation has over twenty million total views to date. @CelesteHeadlee

Additional Resources:

- Website: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- Get FREE shipping on Adichie’s books from our partner bookstore, BookPeople: Americanah | We Should All Be Feminists

More from Women Amplified

- NEW YEAR/ NEW PROBLEMS TO SOLVE! Tell us what you’re dealing with at work or at home and you could be paired with an expert for an upcoming episode of “That’s A Good Question” on Women Amplified! Learn more.

- Sign up for our email list to receive a notification every time a new episode drops.

- Join us in person — or online — at the 2023 California Conference for Women this Women’s History Month. Enjoy powerhouse speakers, multiple networking opportunities, fun interactive exhibits, and a brand-new in-person/ online hybrid experience. Learn more at caconferenceforwomen.org.

Episode Transcript

Laysha Ward:

Chimamanda, it’s such a gift to have you here today. You know, I share your passion for storytelling and the power of words. Now I often say that when we share our stories, when we speak our truth, we learn to celebrate our dimensions of difference and the things that we have in common. What can we do to encourage more people, especially women, to share their stories, our stories?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

So you know, we know from statistics that women read men and women and men read men. I think one of the things we need to do is get, try and get everyone to read women’s stories. So push women’s stories, talk about women’s stories, but also tell women that it’s okay to tell their stories. I think there’s a lot about the way that women are socialized that they sometimes think they shouldn’t occupy so much space. They shouldn’t talk too much about themselves. They should sort of keep themselves back. And and so I think there’s a kind of, that we need to find ways to make it ordinary and normal for women to tell their stories. I think that women’s stories are undertold and under read and underappreciated. And I sometimes think that maybe many of the problems we have would be, and this is maybe wishful thinking, but that many of the problems we have would be if not eliminated, reduced if more people read women’s stories.

Laysha Ward:

How do you practice the kind of listening that drives true understanding? Yes, we’ve talked about needing to read more and having it be a broad variety of our stories, but how do we ensure that people are actually listening to the stories as we want them to be delivered and, and taken in?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

I think maybe I can, I can speak for myself, which is silence when I really, I think it’s so important to be silent when someone else is talking. And I’ve, I’ve found that it’s quite difficult for a lot of people to do. So people are very, very quick to want to sort of, and it’s, you know, it’s very sweet. It’s well-meaning. People want to give their opinion, but often I find that they’re not really listening. What they’re waiting for is for whoever is speaking to stop so that they can say something , right? And, and so for me it’s, it’s, it’s really important to have a kind of, you know, kind of considered silence. When people are talking to me, I’m quiet as I’m listening, like I just, I’m completely quiet and, you know, I want to hear what they’re saying before I can actually say something.

And so I’m not thinking about what I’m going to say, I’m thinking about what they are saying, and it kind of seems almost self-evident and obvious. But, but it’s, I think it’s difficult for a number of people. So I would say we need to practice what I would call a kind of a kind of present silence when people are speaking and even when we read, you know, life is now so quick. You know, time is in such short supply for so many people that even reading is something we do without that kind of considered silence. People read fast and often miss things. And and it’s, it’s kind of a pet peeve of mine when someone, you know, I have someone read something and then I I I’m talking to them and I realize, wait, did you not even read that part?

Laysha Ward:

You know, I’ve certainly experienced that as well. I love how you frame it up by being silent and being comfortable in that silence, I think is something that’s difficult for many of us. Certainly difficult for me, and active listening requires active silence. Really appreciate that perspective. So, following up on that from another standpoint, how do you respond in the moment when it’s clear that someone isn’t listening to you?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Oh, it depends on the time of the month.

Laysha Ward:

Say more about that.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

So if I’m, if I’m not in a good place, I respond by using very sharp language. If I’m in a better place, you know, I say things like, actually my family and I have a joke, which we call the crocodile joke, right? And that’s because when I’m talking to members of my family, my husband, my siblings, and sometimes also my very close friends, when I sense that they’re not listening to me, I say something and I include the word crocodile because that’s just the most absurd thing, right? And if they then turn and they’re like, wait, what crocodile, then I know they’re listening Crocodile

Laysha Ward:

What? Crocodile. So they’re, I’m, I’m about to cry crocodile tears because you made me laugh so hard.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

So I do the crocodile thing because I’m trying to, you know, trip them up. Are you really listening to me? So I’m sort of talking about, I don’t know some, some, I don’t know, government policy, , and I feel like they’re not listening. Then I say, and then the crocodile came out.

Laysha Ward:

I’m going to use that. When the crocodile came out, I, it’s definitely something I’m gonna pick up on after our conversation. You know, communication is a two-way street. It requires patience and discipline and, and definitely listening so that we know that we’re actually understanding, truly understanding what someone is trying to share with us. And I think when we practice this sort of patience and discipline we can gain a deeper understanding of one another. And you’ve also just introduced some humor into the conversation, which I think is always helpful when we are trying to communicate with people as well.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Yes, absolutely. I think humor is, I think humor is an essential part of being human, you know, and it’s something that we all have in common. It cuts across cultures, cuts across, you know, we all laugh, but I also think you know, just, just to sort of add to what you said that we, the listener needs to make an effort, but I think the speaker also needs to make an effort. I think, you know, I think the speaker has a responsibility to be clear, to be engaging as much as possible. And so when, when people are not listening to me, my first thought is, alright, you’re just not listening to me. My second thought is maybe I’m not telling the story in the best way. You know, maybe I’m kind of boring , right? So then you, you need to sort of think about how you’re telling your story. Yes. Because you do have a responsibility to tell the story in the best possible way.

Laysha Ward:

Oh, I love that too. There’s a shared accountability, both in how you’re sharing the information as well as how one is listening. I often talk about the importance of listening to learn and understand versus just listening to win or fix. But, but you are going even deeper and talking about this idea of shared accountability in that communication, which I think is incredibly powerful. So thank you for that.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

I really like that listening to learn and fix. I would argue that there’s a gendered component there, but maybe we shouldn’t talk about that. No.

Laysha Ward:

Well, well, let’s, let’s build on that then. Let’s talk about the gender component in that. What would you, what would you add to that conversation?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

I think it just seems to me that men are more likely to kind of want to fix things and not in the end not really hearing what’s being said. And that may be because I think, and again, obviously we’re, we’re generalizing because they’re always exceptions, but I think if, if I were to suggest to men ways in in which they could improve their listening, one of the things I would say is don’t think about fixing it for now, ,

Laysha Ward:

We can come back to that, but to sort of focus initially on listening to learn and understand in service of a future solution.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Mm-Hmm. . Well, I think, I think really in general listening should be about that, you know, that that should be the goal that we want to understand really and hopefully learn of, of course. But, but we need to understand, I mean, I think that before you can agree or disagree with somebody, you have to actually understand what they are saying. And I, I sometimes feel that what’s happening today sort of in this sort of wall that we live in, where social media is such a, a central part of the way that we have public conversations is that often people actually haven’t heard what’s being said, right? They actually haven’t understood what’s being

Laysha Ward:

Said, or they only see one part of the story, perhaps using your words, a single story, a story that’s being sort of crafted for that particular platform.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Hmm. And I, and I think, you know, that I’ve talked often about the reason I think a single story is dangerous is that it’s not complete, right? And you, you can’t, you can’t if you’re making a decision based on, on incomplete information, then that decision in itself just becomes fundamentally flawed.

Laysha Ward:

Absolutely. That applies in our professional lives as well as our personal lives. And so that’s a really important point to get the full story, which is often complex and layered

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

More difficult. It’s more diffi. I think single stories are easier.

Laysha Ward:

Hmm. Absolutely. You’ve talked about the importance of using the BS or bullshit detector on yourself as well as on others. So tell us more about how we can apply this to our day-to-day interactions with colleagues and others.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

well, maybe with colleagues, maybe we shouldn’t, maybe we should find a more colleague friendly expression. Maybe bullshit detector won’t work, but

Laysha Ward:

. But, but, but it is authentic and real and to the point. So for now, until we rebrand it, let’s just go with the BS detector and talk about ways that we can apply it in our day-to-day interactions.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

You know what I think, I think fundamentally my my case for having a, a good BS detector is really about wanting and, and feeling that we must insist on authenticity and truth and realness. So I, I think it really just means if you feel that someone is bullshitting you to just say, so, I do that a lot. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable, you know, someone says to me, oh, I love your books. And I’m thinking, actually, you haven’t read them often, I can tell, you know, and I’m like, you know, thank you for your love, but you haven’t read them. And then I say, I would suggest that you read first. You know, I, I suggest a book for them to read. And I think it just makes for, I think it makes for a more I don’t know, a more, when we’re not bullshitting one another, then I think that we just live in a way that is more, and I don’t want to sound sort of very morally superior, but I think we live in a way that is more authentic.

And I think it’s so important. It’s, it’s just so in some ways that you’re cutting away the crap, you know? And, and I think life, life is complicated and life is difficult enough. We really don’t need someone just bullshitting us. And, and so really, I would say find ways to name it. And people have different styles, so it doesn’t have to be my direct way of saying, look, that’s bullshit. It could be . I don’t know. People find their ways of communicating, but I think as long as you let the person know, and I think in general, people who are well-meaning sometimes appreciate it because then they feel that they can be more authentic themselves, right? So the person who says, oh, I loved your books, and I’m like, mm-hmm. You haven’t read any, suddenly then feels more comfortable to say, actually, I don’t really read a lot, but I’ve listened to your talks. You know, that’s happened quite a bit. So I think in some ways you also let people not feel the pressure to be something that they’re not.

Laysha Ward:

I think you’re trying to create a safe space to be honest and build a trusted relationship and a trusting learning environment. And instead of just calling people out for the sake of calling people out, you’re actually welcoming them in, in a way that ideally will make them better and you better in a way that, you know, isn’t a shame and blame. It’s really about, you know, opening up a more trusted environment to have real talk.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

I really love that. I love the idea of welcoming them in. I really love that. Yes.

Laysha Ward:

So, girl, this is so helpful. I’m sure I’m going to be able to apply it. And you know, we have another practical question that we received from the audience. And she says, my male boss talks a lot about celebrating and championing women. For some reason, though, it actually comes across as patronizing. So she’s wondering if she should give in feedback, and if so, what should she say? Which is such a great question.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Hmm. It is. See, in some ways I think it’s similar to, to kind of what I talked about that, and this happens a lot, usually around International Women’s Day when people just pop up and start talking about how women should be adored and celebrated, and it’s, yeah. And sometimes I, I just, I’m very close to being nauseated, but that, that’s I, I think how to do that, I mean, obviously it would depend on what sort of person her boss is but whether I think it’s a useful thing to give feedback about that. Yes, I think so, because I, I do also feel very strongly that most of the time when people, when men say things that women find condescending or patronizing or offensive, most of the time men don’t actually even know that it’s offensive or why it’s offensive, you know?

I think maybe what I would say is to ask him what he means, you know, so we should celebrate and champion women. What does that mean? Does it mean that you, are you comfortable with having a woman be your superior? If women are to be celebrated and champion, there’s something about it that kind of suggests the power difference because, you know, you celebrate and champion people who are kind of beneath you in a way, or maybe that’s not how he means it, but I, but I would say ask him, you know, so just say to him, give me three examples of how, what you mean by championing women.

Laysha Ward:

Yeah. I love that you’re talking.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

And then if he, and if, and if he gave the examples, then she could then say, well, can you see how in this second example, it’s actually really condescending? Yeah, I think I’m a believe. Yeah. Sorry, go

Laysha Ward:

On. I’m just gonna say, I think you’re asking or suggesting rather that she asks clarifying questions. Assume positive intent and ask a clarifying question that really allow her boss to be more clear in what it is that he means by celebrating and championing women so that they can have a more honest and direct conversation.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

And to do it. And to start off, you know, start off assuming that he doesn’t mean harm. He might, and if he does, you will find out as the conversation progresses, . But, you know, just I think saying to him, and then again, I think, you know, this is why I believe so much in stories, and often I say to people, let’s go to story. So right, somebody says something and people start to argue, and I’m thinking, all right, let’s use examples. Let’s, let’s use a story. Because often it’s so much more clarifying. And so the examples that he gives her might make her see that actually he doesn’t really mean it in a way that’s condescending, or it might make her see that he’s so bloody patronizing. And then she can sort of call him out and say, you know what? This is just not okay. Yeah,

Laysha Ward:

Exactly. You know, it’s to, to your point, assume positive intent, and then you’ll be able to ascertain if it’s perhaps an unconscious bias or a conscious bias. But, but at least you’ll know where to begin the dialogue with better information. Great, great, great point. So thank you for that. Building on that, there’s a related question that another audience member submitted. She says, I support gender equality, but don’t call myself a feminist because it feels too much of a statement. How can I be a feminist without the negative labels? There’s a lot to unpack in that question, so I would be curious to hear what you would say.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Well, I would say to her, you’re a feminist. Own it, you know, own it. And when I started talking about feminism, I knew, of course that feminism is such a contested ward, especially in the West, where it has a long history. And, you know, feminists are often seen as, as you know, women who hate men or who don’t shave or that kind of thing. And, and, and for me, I, I then kind of had this need desire to kind of reclaim the ward that in the dictionary, it’s, it’s, it’s simple. It’s the belief that men and women should have equal political, social, economic rates. And if you believe that, then you’re a feminist. And, you know, sometimes I worry that women are often too careful. I mean, I suppose the question I would ask is, why is it too much of a statement?

I mean, what is it that you are afraid of? Yeah. you know, it’s easy to maybe think, I don’t want to alienate men by calling myself a feminist, because there’s some men who would be alienated by that. And I think to that, I would say a man who’s alienated by the idea of feminism is the kind of man you don’t want to be with. So, you know, own it. And, and the reason I think it’s also important is that we need a ward around which to rally. So if women are saying, I’m not a feminist, but I really believe in everything that feminism stands for, then we can’t even advocate for things because we cannot then say we’re, we have this word feminism, and these are the goals that that feminism has, and we want to pursue them. If we don’t have the language, if we don’t have the word to to describe something, then we can’t really advocate for that thing.

Laysha Ward:

I love this notion of claiming it and naming it and putting words around it in order to embrace it in a way that allows us ultimately to take steps towards fulfilling it. And so the way that you talk about and are framing a response around feminism is often how I think about racism, which for many is difficult to talk about as well. So really appreciate the way that you’ve helped us think about that. And I’m definitely gonna be thinking through how I use it and hope that our audience finds that equally as valuable. I appre appreciate the vulnerability in the next question from one of our audience members as well. And she says, my company has employee resource groups for women of color, people with disabilities, l GT q plus as a white woman, I wanna support my peers, but I don’t wanna do the wrong thing. What’s the best way to navigate this?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Who? I don’t know, . .

Laysha Ward:

Come on, girl. You can say something. You’ve, I know you’ve got something .

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

I think , see this is I really, actually really appreciate that question because I think it comes from a place of it comes from a place that I really admire and respect wanting to do better, wanting to do well, and, and saying I don’t know how. Right. Which I, it would be lovely if, if, if we all could do that. I think maybe the suggestion I would make would be to ask. So, so in other words, so I mean, I can’t really, I don’t think I can really talk with much I think I can talk about race with more sort of confidence because of personal experience, and I can talk about disability and and sexual orientation and, and gender identity and all of those things. So, so for me with race, if a, if a white woman says to me, I want to be supportive of anti-racism movements, and I don’t know how usually I say, well start by reading.

And I say that because I think it’s important to, to, to understand what it is that you are, you are advocating for, right? And when I say start by reading, I mean just understand what it, what it has meant and what it continues to mean to be a black person in the United States. And, and I think also sort of talk to black people. You, I have friends who are so well-meaning and so fierce, and they’re sometimes making arguments where I’m thinking, I’m the black person and I don’t even agree with you on this . Right? Like, I just think you’re wrong. Right? Right. But, but it’s well-meaning. And they’re just sort of like, yo, yo, we’re fighting racism. And I’m just sitting there thinking, mm. So, so yeah, I would say talk to black people. And it also is very useful to sort of step back in certain places and let black people speak.

There are times when I say that the white friend needs to say certain things. There are things that white people can get away with saying in this country that black people cannot. And so in those cases, I think if, if, so, I have a joke with a white friend of mine who sometimes we’re talking about race, and, and I say to her, well, all right, now you need to talk because these people will not listen to me. You need to talk now. You know, you need to use your white privilege for good. But there are other times when I think well meaning white people, that there is sometimes the risk of kind of usurping the conversation, taking it over, making it about sort of the white goodness. And I, I don’t think that’s a very useful thing. So, so I’m not sure, yeah, I’ve kind of rambled a bit, but I would say, you know, talk to people, talk to black people.

And also I would say learn like, and, and I don’t mean learn, you know, young people now say things like, go and educate yourself. And I don’t even know what they mean, but , but I can tell you what I mean by learning, which is read history. You know, I would say I could ma maybe recommend three books because I think it’s important to have context. And I even speak for myself because when I came to the us now almost, I don’t know, 25 years ago to go to college, I didn’t really understand race in America because I was Nigerian. And in Nigeria, we do not have race as an identity. Yes. Do it different. Yeah. And so I came from a place where my identity was IK and Catholic, so, you know, ethnicity and, and religion. And then I came here and suddenly I had this thing where I was the black girl.

Cause I was in Connecticut, which was, you know, not terribly black . And so I, I had to learn and I learned by reading, and then suddenly I understood things. So suddenly I understood, oh, so that’s what that what, what a Milan joke was about. And I understood, oh, so that’s why in certain contexts, fried chicken is offensive. I did not understand that first. And so that’s why I say it’s really important to read, you know, just really read before you go off, you know, sort of on the rallies to do the rah rah rah or fighting racism thing.

Laysha Ward:

Well, thank you for that. No, it, it requires building empathy and understanding and, and then knowing what to do with it, I think gets at your point around sometimes you need to be the messenger. And other times that isn’t the appropriate role for you to play. So, you know, to the question ask, you know, being a great ally, which is what she’s trying to be, is, is multi-layered and isn’t a one size fits all sort of journey. But, but educating oneself, building empathy, trying to sort of make understanding a part of your daily journey allows you, I think ultimately to apply what you’ve learned in ways that help us all figure out what our roles are in those conversations and in the actions that pursue as a result of it. I, I just think we can’t let our fear of saying or doing the wrong thing stop us from doing anything at all, which is often what happens.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Bravo, I think you’ve just, I just think that’s perfectly said. And, and you know, you said something about layered, and I, I, and I think it’s important also to be comfortable with the idea that it’s not going to be simple or it, it is layered, it is complex and, and we shouldn’t expect it to be otherwise, because how can you deal with I think for example, that having learned American history, that really the basis of this country is anti-black racism. I, I believe that, and I, and I can, I can make the case for it, right? And it’s such a complicated thing that’s so deeply rooted, so that in talking about it and trying to combat it, it cannot be easy. It’s not an easy thing. And so I really love this idea. And you put it so well, we shouldn’t be so terrified of saying the wrong thing that we don’t say anything at all, because it is likely that we will say the wrong thing. Yeah. But I think what, what’s pos what, what’s important is, you know, are we learning? Are we when we say that wrong thing and we ask questions, do we then, you know, hear what’s been said? And I think that the way that public sort of conversations happen now, people are so scared of, of saying the wrong thing, that they just stay silent. And it worries me that that real movements for change are now sort of almost being sabotaged by people’s fear. Yeah,

Laysha Ward:

I would, you shouldn’t be, I would agree with that. As we discussed earlier, sometimes there is a moment to be silent, but there are also times when we need to have our voices heard. And, you know, a situation we all face from time to time that you and I have just started to talk about has to do with missteps in our communication. So how do you recover when you say the wrong thing?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Well, by saying, sorry. Yeah.

Laysha Ward:

, yes. Amen to that. I think

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

That, I think, I think there’s such power in a genuine apology. But I also think that even the idea of apologies have become just, you know, people just think, you, you, there’s, there’s kind of a cynicism now where people just sort of say, oh, I’m a apologizing. But I mean, really genuine apology. But also I think when you, when I can speak for myself, for example when I’ve said things that I realize were wrong, , often I’ve realized because somebody has made me see that they’re wrong. And and by the way, I have to tell you, I’ve had to practice this because my, you know, you need to practice it, but there’s a kind of grace in saying thank you to the person who’s made you see that you were wrong. Right. which means a kind of willingness to accept that I don’t know everything, right?

I think I know a lot , but I don’t think I know everything. . and, and I think, you know, there’s a kind of again, it sometimes feels to me that in the end it’s about intent. Like what’s the point, right? I, I ask this a lot about many things. What’s the point of having conversations? What’s the point of talking about social justice? You know, I say to myself, what’s the point of talking about racism, feminism, homophobia, what’s the point? Right? And of course, the point is to contribute, to ending it, ending these things that we think are wrong. And if that is the case, then in having conversations, the intent is to get somebody to understand you and to be understood by that person. And so when I say something that I think is wrong, I, my thinking is, well, what’s the point?

So what I’ve said is getting in the way of achieving my point, right? Which means that I need to backtrack, you know, apologize, figure out what the real thing is, what the right thing is. And I think in general, we should maybe start by just, I mean, I, and this is the thing for me, being a fiction writer, I kind of I, I enjoy, I, I celebrate, I luxate in the fact that we are not perfect. Yes, yes. And we’re not, I mean, people who read a lot of fiction know this, we’re human, we’re not perfect. And so I think just starting with that as premise, it just feels to me that a lot will be better. When I teach fiction, I usually start by telling my students, we’re going to go around and you’re going to tell me two horrible things you’ve done. And then at some point, sometimes it gets really, you know, interesting. And then I say, all right, tell us two horrible things that a friend of yours has done if you don’t want to talk about yourself. But it’s really . It’s really about starting off with our flawed ness as premise.

Laysha Ward:

I like to say we are perfectly imperfect. And you know, I think it’s really important as we’ve been discussing to know and remember that we’re all human and make mistakes, but that we can learn from those mistakes. I think that certainly is the key takeaway. Thank you so much, Chimamandamanda. I could talk to you for hours.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Thank you, Laysha. You’ve been fantastic.

Laysha Ward:

Incredibly fortunate to have had this time with you, and I know that I’ve personally benefited from it and know that our community here has as well from your stories and your wisdom. And I hope that we have the opportunity to reconnect in the future. Cause it’s certainly been a gift.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Thank you, Laysha. Thank you. And I really do hope that we have a chance to, I hope our paths will cross

Laysha Ward:

Again. As do I, as do I. Take care.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie:

Thank you. Take care.